Ayodele Casel in “Freedom…in Progress,” photo by Steven Pisano

I was asked recently what trends I was seeing in dance, to which I blurted out, without much thought: so much hugging! This year everyone seemed to be hugging, from the characters in Justin Peck’s Illinoise to the dancers in Caleb Teicher’s A Very Swing Out Holiday and Kyle Abraham’s Please Lord, Make Me Beautiful. I confess that the anti-sentimentalist in me cringes at such generalized, soft-edged displays of emotion. But even this cynic can intuit a reason behind the comforting gesture: we are all suffering from an acute sense of malaise. Wars, the rise of right-wing, populist leaders, financial insecurity, the ubiquity of social media, the undeniable evidence of a worsening climate, intractable cultural divisions and a host of other things have us on edge. Maybe we all need a hug.

The second trend I noticed was less existential, but no less pronounced: dancers, dancers, dancers. There have always been great dancers, but lately it has seemed as if extraordinary performers were blossoming before us on the daily. In the realm of ballet alone, there are four young dancers whose every performance feels like essential viewing: at New York City Ballet, Mira Nadon; and at Ballet Theatre Chloe Misseldine, Catherine Hurlin, and Cassandra Trenary. What’s even better, they couldn’t be more different from each other. Nadon is a force of nature, driven by theatrical instincts and hunger for space. In everything from Tzigane, Mozartiana, and Liebeslieder Walzer to Ratmansky’s new Solitude, you simply cannot take your eyes off her. Each début revealed a dancer who moves with exciting amplitude, carried by the music, lost in its secrets and subterranean flow.

Mira Nadon and Peter Walker in Balachine’s “Liebeslieder Walzer.” Photo by Erin Baiano.

Then, there was a week during Ballet Theatre’s summer season in which I saw three interpretations of Swan Lake, each so different and fresh it felt almost like a different ballet. This, despite the great limitations of the company’s sub-par production. (Might the company’s new director, Susan Jaffe eventually replace it? Next year there will be not one week, but two, in which to contemplate its deficiencies.) One of these performances was led by Isabella Boylston, who, in her late thirties, has entered a new phase in her dancing, in which her personality flows through her at every moment. It was evident from the sensual way she arched her upper body in her partner Daniel Camargo’s arms and in her playful fouettées; they felt like the natural expressions of feeling or thought. I loved the way she caressed Camargo’s face during the seduction scene—there is not a prince in the world who could resist.

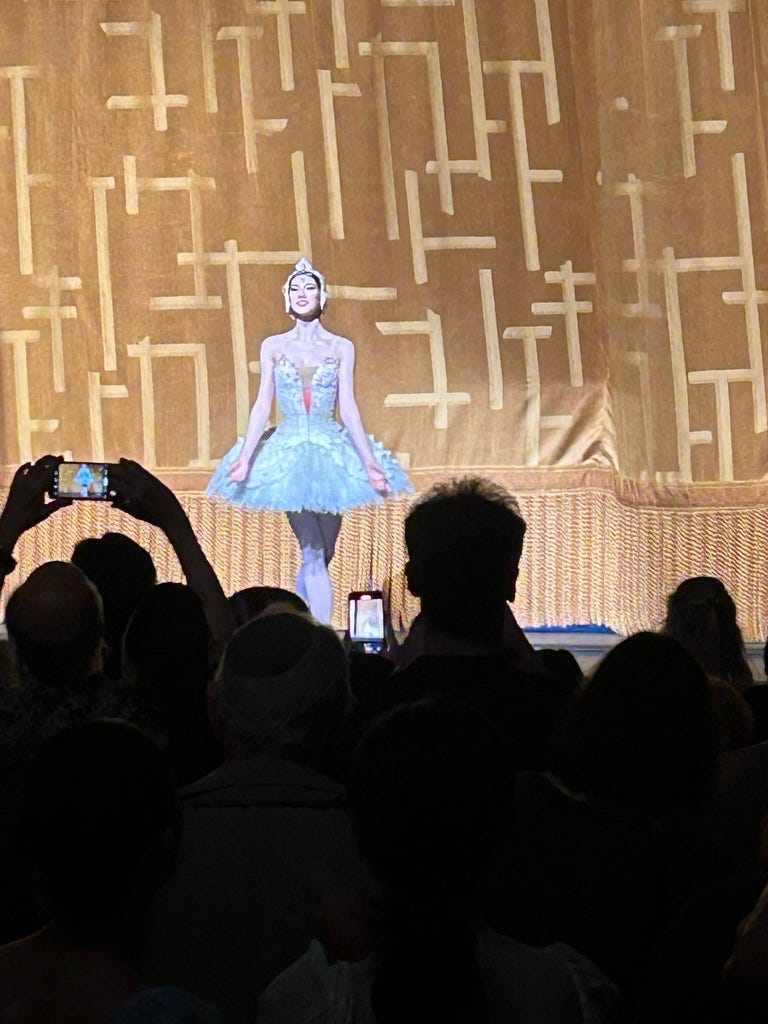

Chloe Misseldine, after her New York début in Swan Lake with American Ballet Theatre.

Days later, Chloe Misseldine had her New York début in the role, and Catherine Hurlin returned to it one year after her own début. Both were extraordinary. Misseldine used her exquisitely long lines—neck, arms, back, legs—and beautiful face to create an Odette that was almost otherworldly, but at the same time completely natural, unmannered. She is an uncommon technician who seems incapable of taking a wrong step, except that in her case technique isn’t an end in itself, but rather part of a beauteous whole. The next day, Catherine Hurlin performed the dual role of Odette and Odile with such clarity of purpose it was almost as if she had been speaking lines. Hurlin is an actress through and through, able to transform herself from scene to scene. Particularly astonishing was how, moments after she had seduced the prince, with flashing eyes and triumphant backbend, she returned to the lake in the form of a young woman whose heart had been thoughtlessly tossed aside and trampled on. It was hard to believe we were watching the same dancer.

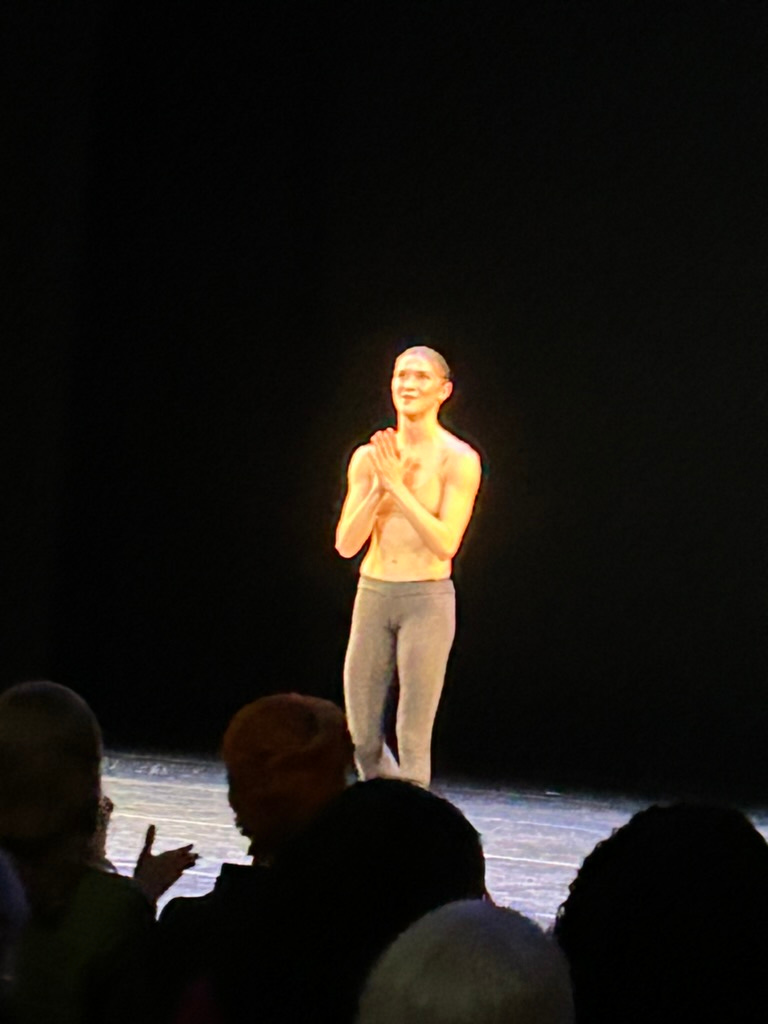

Cassandra Trenary, after State of Darkness, at Fall for Dance

Trenary is a different kind of ballerina, one who seems to chafe at the conventions of ballerinadom. She wants to be more than a maiden or a spirit or a young woman discovering love for the first time. So she finds expression on the fringes of the repertory, in works like Helen Pickett’s Crime and Punishment, in which she danced the role of the tortured killer Raskolnikov. But her real triumphs take place beyond her home company (ABT), in outside projects like Molissa Fenley’s State of Darkness a nearly half-hour-long modern-dance solo set to Stravinsky’ Rite of Spring. Here, Trenary’s ferocity was unleashed and distilled, reaching a blinding intensity. She performed the solo this fall at Fall for Dance. Not once did her energy or interiority lag; it was as if she were circling and circling around something essential, buried deep within. Sometimes, as I wrote after the show, it felt as if we in the audience were able to see through her skin into her muscles, tendons, and bones. Her performance was fascinating, and a little scary.

Roman Mejia, Mira Nadon and Chun Wai Chan in Tiler Peck’s “Concerto for Two Pianos.” Photo by ErinBaiano

From time to time ballerinas reveal themselves to be choreographers, too, and this is cause for celebration, especially when the product of their labors is good, as it was with the premiere of Tiler Pecks’ Concerto for Two Pianos, a big, ambitious, abundant new work set to Poulenc for New York City Ballet. Not only does Peck’s ballet celebrate the company for which she has danced for two decades, but it gleefully shows off the particular talents of several of her younger colleagues: Mira Nadon’s glamor, Roman Mejía’s charming bravura, Chun Wai Chen’s suave partnering, Emma von Enck and India Bradley’s quickness and pin-prick clarity. The ballet also proved that Peck knows how to grapple with a big piece of music, drawing out its themes, playing with them, building a satisfying whole. Better yet, it’s a ballet you can enjoy more than once, with pleasure.

Sterling Harris, Gisele Silva, Naomi Funaki, Ana Tomioshi, Orlando Hernández, and Roxy King in Music From the Sole's “I Didn’t Come to Stay.” Photograph by Steven Pisano

Pleasure was a big part of the experience of seeing Music from the Sole’s I Didn’t Come to Stay, the company’s first full-length evening at the Joyce Theater. The show combines the rhythmic play and improvisatory freedom of tap with the rhythmic, melodious, joyous sounds of Brazilian samba, funk, and jazz. The company is led by Leonardo Sandoval (from São Paulo, Brazil), a dancer, and Gregory Richardson, a musician. Around them they have gathered an ensemble that projects inclusivity and fun, and where the dancers bring all of themselves, becoming part of a friendly and eclectic whole. (All without hugging!) It’s like a party for all the best dancers who also turn out to be lovely, generous people, eager to play with others.

Tap is definitely having a moment; each show seems to open up new channels in the imagination. The highlight of the Joyce Theater’s Max Roach tribute back in April was an extended tap interlude by Ayodele Casel, Freedom…in Progress, in which she performed a structured improvisation in response to a recording of Roach’s collaborations with the pianist Cecil Taylor. The rhythms she created unspooled in dizzying landscapes of sound. Their patterns didn’t follow those of the music, which were already complex enough. Instead, the dance was like a counter-melody, a commentary, a supplemental layer, a response, to Taylor and Roach’s aural meanderings. The solo lasted a good long while, and was challenging (even exhausting) to follow, but you wanted to stay as alert as possible, to take it all in, to follow the yellow brick road all the way to its final destination.

New York City Ballet in Alexei Ratmansky’s Solitude. Joseph Gordon and Theo Rochios are in the front left. Photo by Erin Baiano

Alas, the bleakness of our current moment cannot be denied. There was a work early in the year that looked this reality directly in the face, in a way we seldom dare to. In his first work as artist in residence at New York City Ballet, Alexei Ratmansky took on one of the most difficult subjects: war and death. This is almost always a bad idea. Dance has difficulty rising to the occasion. And dances about life and death often come across as ponderous. Let alone dances set to Mahler. But this ballet, Solitude, inspired by a real photograph of a man holding the hand of his dead son at a bus stop in Kharkiv, Ukraine, escaped those traps. The first section, set to the funeral march from Mahler’s first symphony, was almost surreal. Marionette-like figures moved across the stage, pulling at each other, falling, teetering on pointe. A woman was tossed through the air. A young man receded from view, performing a stiff-legged dance of death. All was confusion, dissociation. In the second section, set to Mahler’s familiar Adagietto, a man—who, having lost his son, was the embodiment of solitude—danced an aching solo, in which he repeatedly and effortfully gathered up his energy, only to tilt forward into space, grab at the air, scratch the earth. All this sounds melodramatic, but in reality it was something far worse: chilling, laborious, hopeless. By the end, you felt almost sick.

I can’t think of another ballet that conveys so much sadness in such a quiet, unflinching way. It is a stark reminder of the real suffering that exists in the world, and of both art’s ability to convey that suffering, and its inability to do anything to alleviate it. Art is helpless. It’s all we have. No wonder we all need a hug.

Dear Marina, Your reviews often accompanied with photos, have helped me get through the year. You incisive, buoyant writing has often lifted me out of the gloom. You hug me with your words and I thank you, thank you, for your "you are there" writing that I often carry with me during my days. Your devotion to beauty is a blessing.

Beautiful summation of a difficult year—but one brightened by some balletic (and other dance) highlights.