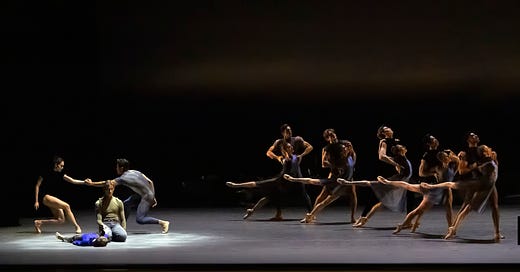

New York City Ballet in Alexei Ratmansky’s Solitude. Joseph Gordon and Theo Rochios are in the front left. Photo by Erin Baiano

I wondered last night, as I sat somewhat stunned after the premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s new ballet for New York City Ballet, Solitude, how its crushing effect had been achieved. The collision of art and reality is an uncomfortable one, especially when the reality being depicted is something as overwhelming and deadening as war. There are so many things that can go wrong—over-sentimentality, falseness, exploitativeness—and the stakes, when the reality of the thing itself is right there in front of our eyes, are terribly high.

I’m not sure how Ratmansky managed to thread this needle in his new ballet, but somehow he has done it. Further viewings will reveal more of the details behind the sensation it produces: a tautening in the chest, a tension that builds and builds over the course of the ballet’s two parts and leaves your mind almost blank. The final effect is a confusing mixture of admiration and deep sadness. It is a masterful work, perhaps the most moving I’ve seen on the subject of war, containing one of the great male solos in any ballet.

I had watched a couple of rehearsals, and I’ve written a lot on Ratmansky and spoken to him at length for my book, and yet, I wasn’t prepared. I can explain the essentials: The ballet was inspired by a photo from the first year of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in which a father holds the hand of his dead thirteen-year old son as he kneels by a bus-stop in Kharkiv that has been struck by a Russian missile. The man sat there for hours, his eyes empty, as people tried to console him and to convince him to let go of his son’s hand so he could be taken away.

Joseph Gordon with Indiana Woodward, KJ Takahashi, Sara Mearns, and Chun Wai Chan in Alexei Ratmansky’s Solitude. Photo by Erin Baiano

The musical score is made up of two movements from two Mahler symphonies, the funeral March from the first symphony, and the “adagietto” from the fifth. The march contains contrasting sections that splice together an emotion-less dirge with grotesque klezmer dances and haunted melodies evoking love, or comfort, or better times. There is an elegiac melody that echoes Kindertotenlieder. (The contrast of grotesquery and sadness is very Shostakovian.) The “adagietto,” famous from the movie Death in Venice and elsewhere, is a love elegy composed of shimmering waves of melody, sustained by the strings of the orchestra.

What is interesting is what Ratmansky does with this music. During the entire first section, the dancer in the role of the father, Joseph Gordon, kneels at the far left of the stage, holding the hand of a young boy from the company school, Theo Rochios, who plays his son. They are in street clothes. A chain of figures enters from the right, in various shades of gray and black (designs by Moritz Junge), bending, twisting, pulling, and falling, with sharp, puppet-like movements. A woman’s body seems to bend and break as she pulls away from her partner; a man staggers with arms behind his back, like a prisoner. Eventually they form a frieze, a diagonal line with the women’s bodies lying flat on the ground and the men gesturing toward them stiffly. A woman—the stunning, brave Mira Nadon—is tossed across a vast, gasp-induing space, with great force, and caught.

Most of this section is made up of images: broken bodies, scenes from life. A woman (Ashley Hod) sits next to the man for a while, with a hand on his shoulder, completely still. Two women (Sara Mearns and Nadon) stand behind him with their bodies and heads curved to the side, like saints in an icon. A man lies crumpled on the ground like a dead soldier. A clump of four, perhaps a family, poses for a portrait. Eventually, the boy is led away by two women (Nadon and Mearns), down a diagonal that cuts a path amid the kaleidoscope of movement that unspools around them. A soldier-like figure, KJ Takahashi, does a sharp dance, stiff-legged and stiff-armed, backing further and further away, until he too is gone, leaving the man alone.

Who are these figures? Spirits perhaps, or phantoms, or thoughts, or memories, flashing through the man’s mind. At one point they toss the boy from person to person; they are there to convey him to another place, far from the living. (The image is shocking.) They offer neither consolation nor meaning; they simply exist around the father, or within him, in his confused and broken mind. I was reminded of the photograph of the father who lost his son in Kharkiv. What thoughts went through his mind in those awful hours after his son was killed?

Mira Nadon and Sara Mearns in front, while School of American Ballet student Theo Rochios is passed from person to person in Alexei Ratmansky’s Solitude. Photo by Erin Baiano

Then, in the second section, set to the adagietto, the dark backdrop lightens (lighting by Mark Stanley), turning gray. The man (Joseph Gordon) rises, still lost in a dream, to perform a long, almost never-ending, solo. His eyes cast downward, Gordon tilts to one side, as if peering into an abyss, then gathers his strength into a deep plié, leaping from leg to leg, driven forward by a frantic energy, reaching down, reaching up, spinning, jumping, spinning more. The energy of each phrase of movement rises and falls with Mahler’s long, drawn-out musical phrases, finding a climax and release in each one, while at the same time building a growing wave of tension. Gordon prolonged this tension, creating a flow between each movement and phrase, a momentum built out of inner focus combined with phrasing and muscular control. Like grief, the solo kept renewing itself, in a loop.

He returned to the spot where his son had lain, lay down there, face down, moved his arms as if creating snow angels. The others repopulated the stage, and he performed the solo again, now with the boy, hand in hand, before they walked the same diagonal amid the crowd of dancers. Sara Mearns, a kind of angel of mercy, led the way. And then, a flash. Bodies flying, bending, falling. And a return to the original scene, the father, the son.

Ratmansky, not an artist known for dwelling on the darker sides of existence, has somehow found a path inward to something very true, very real, and terribly stark. So real, in fact, that it seemed like a prefiguration of the news, just hours later, that the Russian dissident Alexei Navalny had “died” (aka been killed) in Russian custody. It’s not often that ballet and grim reality coexist in such close proximity.

Solitude was the middle work in an evening that also included Jerome Robbins’s Opus 19/The Dreamer, created in 1979 and danced here by Taylor Stanley and Unity Phelan, and George Balanchine’s Symphony in Three Movements, from 1972. Opus 19 too contains an extraordinary male solo, created originally for Baryshnikov. Like Ratmansky’s protagonist, Robbins’s dreamer seems to conjure the other characters in the ballet, including a ghostly woman who appears and disappears through a cloud of dancers. But his torment, poignantly expressed in Prokofiev’s violin concerto (singingly played by Kurt Nikkanen), is of a poetic and metaphysical sort. The man twists his upper body, stretching out his arms with open palms or in fists. Stanley’s dancing had an intriguing wafting quality, a creature-like lack of sentimentality. Dancing with Phelan, they twisted and curled around each other, as if possessed by an external force. Could there be a connection between this ballet and Robbins’ Dybbuk, made just a few years before?

Symphony in Three Movements, which came after Solitude, looked pallid, perhaps under-rehearsed. But its lines and squares, its buoyant energy, and the wonderfully exotic pas de deux set to the middle movement of Stravinsky’s wartime symphony, came as a relief. Here is a clear example of how art can create a sense of luminous order. “Everything is under control,” it declares. Life is a game. If only it were so.

Thank you, Marina.

The entire review resonates in the harrowing week on Earth we just completed. Add this writing about ballet to the deluge of words honoring Navalny. And be glad dance is a participant in our collective grieving.

Erin’s photos as always are outstanding.

This is very powerful to read--the photograph, the heightened experience of viewing, the convergence of political events preceding and then entering this piece. Thanks.