What's in a Dance

"Dances at a Gathering" and "Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet" at New York City Ballet

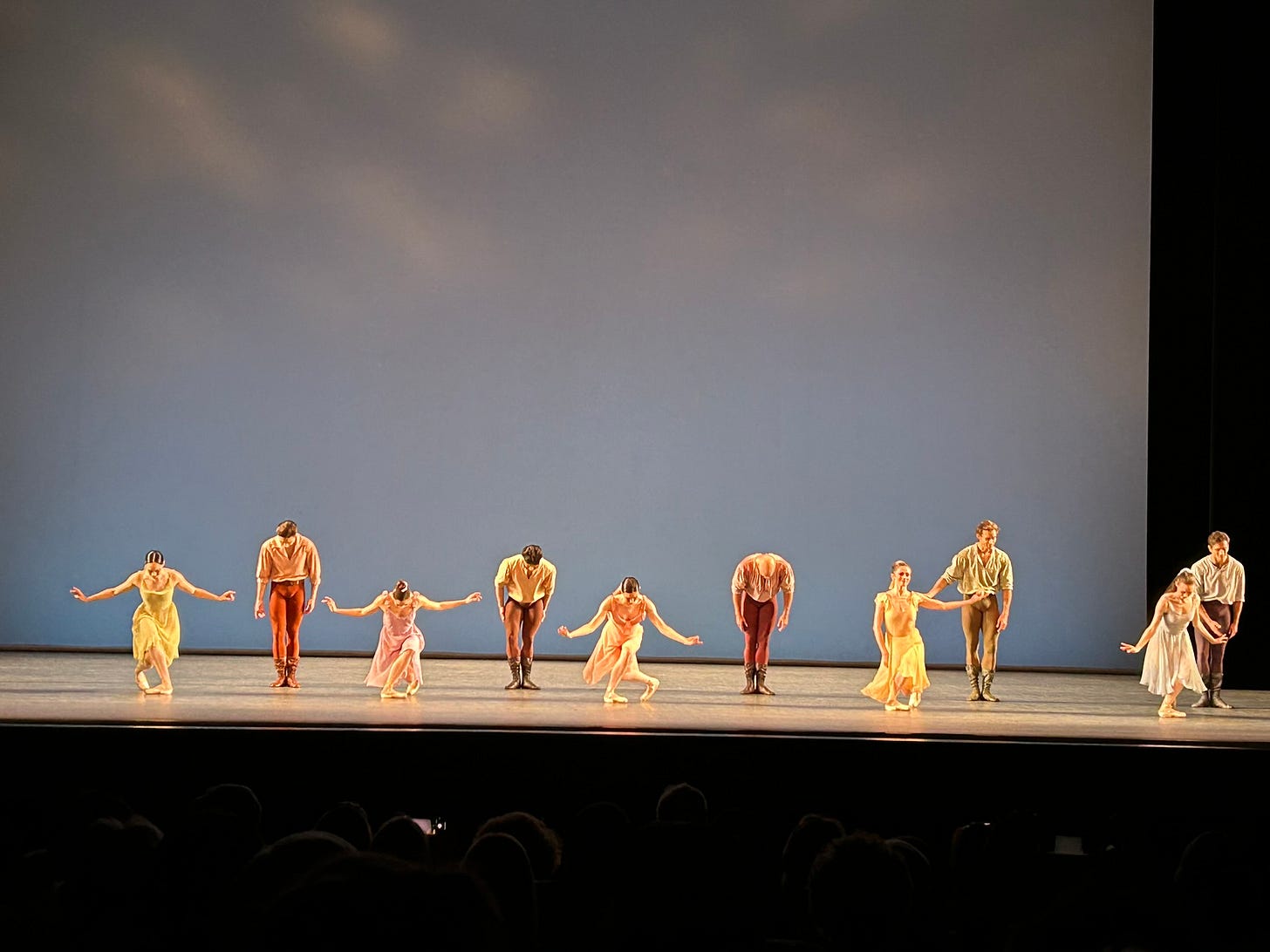

The April 26 cast of “Dances at a Gathering”: Mira Nadon, Andrés Zuniga, Unity Phelan, Roman Mejía, Tiler Peck, Tyler Angle, Megan Fairchild, Alston MacGill, Harrison Coll.

I’m reminded again and again of the delicate and elusive nature of casting, and how it can affect our perception of a work of art. Two days ago (April 26) I watched a performance of George Balanchine’s Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet at New York City Ballet that left me, for the most part, cold. The next day, at the matinee, all of that ballet’s virtues rose to the surface. Not that I would care to see Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet too often—it’s long, and for long stretches, even-toned—but suddenly I could see the point of it, beyond the vaporous prettiness of pink tulle and ribbons, and the fun of the Hungarian-“gypsy”-kitsch finale.

Then there are ballets like Jerome Robbins’s Dances at a Gathering that somehow manage to transcend casting, perhaps because the music (Chopin piano pieces) is simply so very beautiful and the mood so deeply atmospheric. (The pianist on April 26 was Susan Walters, who knows the ballet like the back of her hand; Hanna Hyunjung Kim gave a sensitive, nuanced performance on the 27th.) I find myself being sucked into its world, like Alice traveling through the looking glass, as soon as I hear the first notes of Chopin’s Op. 63 No. 3 mazurka. What Robbins has done is magical: create a world, but then give the viewer the space to project his or her thoughts into that world. The dancers’ steps and interactions are just suggestive enough, but also vague enough, and simple enough, to allow room for dreams, memories, and feelings to come and go. I always feel that watching Dances is like being immersed in a waking dream.

How does Robbins manage this? Well, in part through simplicity. So much of this ballet consists of walking, or running, or skittering. Often the dancers are almost still, as if lost in thought, or absorbed in the act of watching each other. Sometimes they move only their arms, or one arm, or one foot. The ending is so masterful: in ones or twos, the dancers walk out onstage, gather together, and then look up at something that crosses the “sky” above the horizon, then out at the audience, and then down. One arm traces a generous arc; the wrist flips, as if checking for raindrops. Each time, as you watch them, you imagine something different. At these performances it seemed as if the dancers were thinking of the wars that loom on our own horizon, remembering those who have died, and, peering at us from the past, asking us to remember them.

So much of the ballet seems to be about memory. In the opening, a man walks on, takes a step or two, and then seems to retrieve the choreography from a space deep within himself. The “woman in green” dances alone, as if remembering past glories and past lovers. A man arrives in the middle of a dance for three women, as if conjured by one of them, because she has just been thinking of him. Then he leaves, but his presence remains, suspended in her aura of sadness and loss. That sense of loss, so central to Chopin, permeates the ballet and is the main reason it never sinks into mere loveliness. But there is so much loveliness, from the simple dresses of the women to the way the dancers engage each other with their eyes, to the magical lifts that come out of nowhere. A man places his head on a woman’s chest. Three women link arms, and for a moment they become a Botticellian image of the three Graces.

Still, casting does make a difference; certain dancers subtly color the choroegraphy. Both of the casts I saw contained débuts, the most promising of which was Mira Nadon in the role of the woman in Green, a figure who, unlike the others, dances alone, driven by her imagination and fancy. As usual, Nadon immediately made it her own, dancing it with a slight sense of irony, as if amused by her own glamour as she tapped a foot, offered a hand, snapped her fingers. (However she only danced the first of two solos assigned to that character; the other was danced by Megan Fairchild. Perhaps, having stepped in for an injured dancer, she hadn’t yet learned it?) Andrés Zuniga, in the corps, danced with clean, buoyant jumps, and wonderfully crisp transitions. Alston MacGill projected a yielding softness, full of hope and sweetness. Roman Mejía received a well-deserved burst of applause for his airy, easy, windswept jumps in his solo as the “boy in brown,” and he and Tiler Peck were wonderfully relaxed and tender in their pas de deux. But Mejía, the first dancer to walk onstage, isn’t yet able to create the impression that he is imagining the entire ballet into existence.

Of the returning cast-members, Tiler Peck was the greatest revelation. After returning from an injury, she’s dancing with greater simplicity and openness, while losing none of her dazzling precision and musicality. Megan Fairchild, at nearly 40, is quick and girlish as ever as the girl in apricot, who dances the breathless, skittering “giggle” dance. Unity Phelan has a beautiful dreamy quality. Anthony Huxley (the other boy in brown) danced with his usual elegance and polish. But both Tyler Angle and Adrian Danchig-Waring had off performances; Angle had trouble with turning jumps and flubbed one of the big lifts in the spectacular Grand Waltz. Danchig-Waring looked strained at times, and his partnering was a little labored. Ashley Bouder, who has been absent from the stage for an extended period, is still finding her way back. All in all, the April 26 cast, led by Mejía, was tighter and made more of an impact.

As for Brahms-Schoenberg, here the casting made all the difference. This evocation of Austro-Hungarian grandeur set to Schoenberg’s orchestration of Brahms’s First Piano Quartet in G minor, opens to a vista of Schönbrunn Palace and gardens, complemented by draped curtains and fin-de-siècle chandeliers. Each movement is led by a different couple, augmented by the corps de ballet, who created lovely formations: lines and garlands and portals and forests of women. On April 26, the three first sections blurred together, piling on more and more Austrian schlag. But at the matinee the following day, the three opening movements’ contrasting qualities came into relief. Alexa Maxwell and Peter Walker (both débuting), brought the glamor, while Miriam Miller, in the soloist role, was pliant and expansive, a kind of Viennese Lilac Fairy. Mira Nadon and Gilbert Boden III, danced boldly, their expansiveness echoing the sweep of the music. Megan Fairchild and Roman Mejía harnessed the martial quality of the third section with fireworks of their own.

Sara Mearns and Andrew Veyette and the rest of the April 27 matinee cast of “Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet”

Still, the “Rondo alla Zingarese” (rondo in the “gypsy” style) is the showstopper, the number that leaves everyone happy. To Hungarian-folk-style dance music, the soloists and ensemble leap and kick and click their heels, as ribbons and skirts fly. The choreography is unabashedly kitschy, and looks like great fun. Both casts were led by experienced dancers. Sara Mearns, partnered by Andrew Veyette, was proud and playful, and wonderfully grounded. She paced herself, taking a little time here in order to make the next moment just a tiny bit more exciting. Unity Phelan, partnered by Tyler Angle, infused her dancing with a kind of cover-girl glamor.

Either way, it worked.

I love this writing which goes far in compensating for not seeing the performances. Wonderful description through the eye (and hand) of a perspicacious viewer.