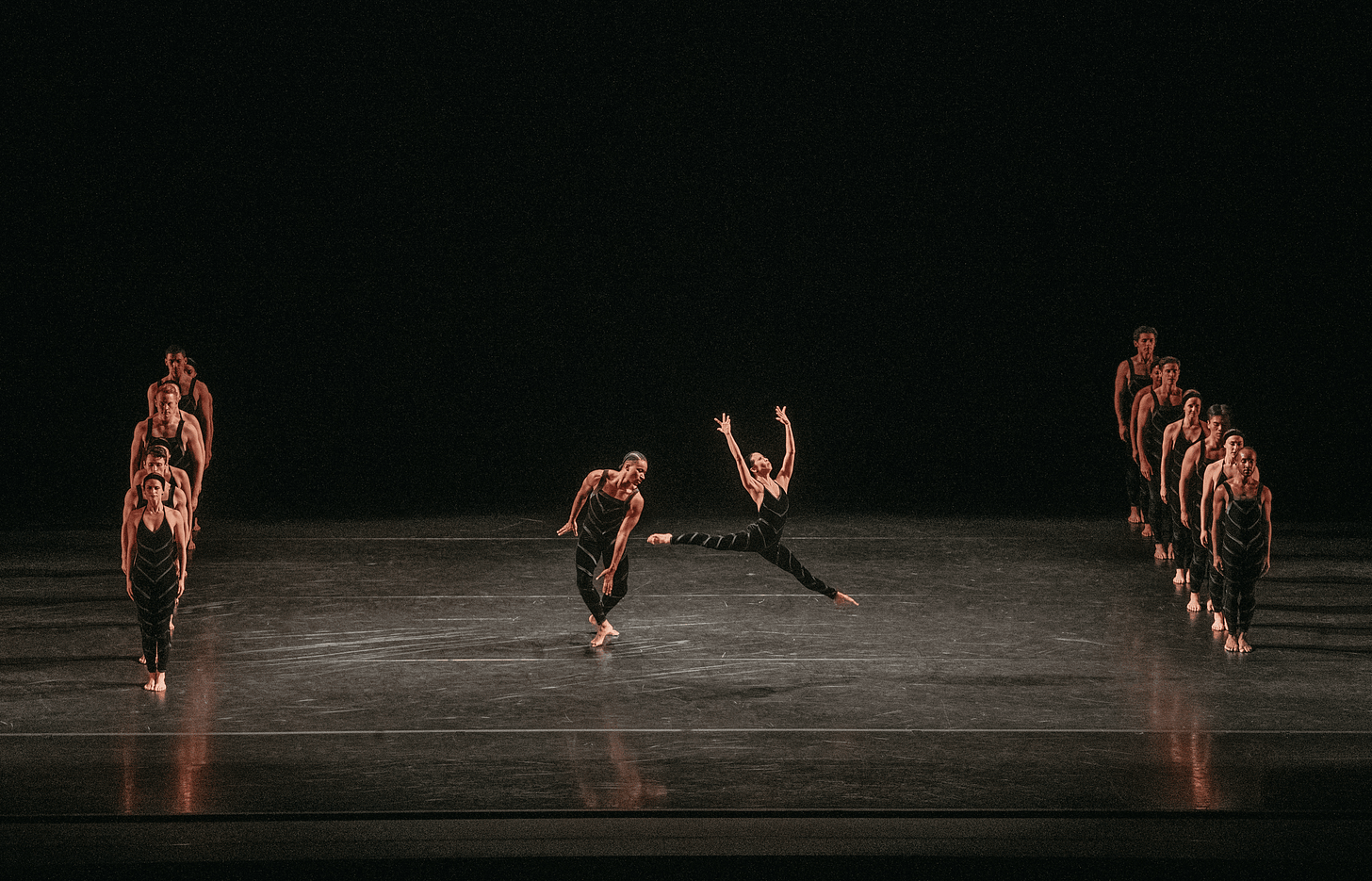

Devon Louis, Madelyn Ho, and the cast of “Promethan Fire.” Photo by Jayme Halbritter

There was much subtext in Michael Novak's words at the Paul Taylor gala (Nov. 6) at Lincoln Center. Diversity, community, love, resilience, generosity of spirit—all figured prominently in the speeches. We all know what had happened the day before. The jury is out on whether art can change society, but what it can do, and always has, is offer both a respite and space for the spirit, and, at least in some cases, a model of behavior. As Balanchine said, "la danse, c'est une question morale." Seen in that light, both premieres, Lauren Lovette's "Chaconne in Winter" and Robert Battle’s “Dedicated to You” offered hopeful, expansive visions of humanity. “Chaconne,” a duet to a rockified version of Bach’s Chaconne from the second partita (played by the heavily amplified Time for Three trio), had two dancers, Madelyn Ho and John Harnage, in unisex sparkly costumes (by Mark Eric), spinning and revolving around each other, fingers shimmering like snowflakes, torsos bending and undulating. Suspended in Brandon Stirling Baker’s light, they watched, respected each other’s space, delighted in each other’s movements, and only occasionally touched. Robert Battle’s solo for Jada Pearman—its title is “Dedicated to You”–was a tribute both to Battle’s teacher, the Taylor dancer Carolyn Adams, and to Taylor's movement style: there were the beautiful, curving shapes, the scooping torso, the silken transitions, the sensual and grounding use of the hips, the strong back. Pearman’s performance was both inward and magnetic, but also, like many Taylor dances, heroic. Not sure how she made it to the end of the three-part work, set to Bach and Sarah Vaughan’s “Dedicated to You,” though it is true she visibly tired by the end. Afterwards, it was announced that Battle, until recently head of the Alvin Ailey company, will become resident choreographer at Taylor, along with Lovette. Even so, both pieces, though well-danced and filled with a reassuring humanity, paled in comparison with the final work, Taylor’s majestic and structurally awe-inspiring “Promethean Fire.” Watching it is like watching architecture in motion.

Devon Louis and Maria Ambrose in “Aureole.” Photo by Steven Pisano.

Two days later, on Nov. 8, the company performed four works, Taylor’s “Aureole”; “Funny Papers,” “amended and combined” by Taylor from material generated by his dancers; an homage to Loïe Fuller by Jody Sperling; and Lauren Lovette's new “Recess,” with designs by Libby Stadstad and lighting by Brandon Stiring Baker. Again, I was struck by the clarity and sense of purpose in the two Taylor works. Somehow, I am seeing them with more clarity this season than I have in some time. Perhaps because most of the company has only been around a few years, the dancers seem to be engaging with the technique and the ideas in a particularly lucid way. Aureole, set to Handel, provides a sort of vision of heaven, a luminous space of tenderness, wit, cooperation, and human potential, all animated by muscular and athletic technique: balance, stamina, fluidity, strong legs, strong backs. It offers a sense of order in a world where there is none. I'm always reminded of the fact that Paul Taylor was a swimmer; he had a powerful understanding of how the back connects to the legs, the arms, and to movement itself. Devon Louis performed the famous Taylor adagio, quietly, poetically, though his transitions were not as seamless as I remember in other performances. I loved the way he placed his hand on his partner’s (Maria Ambrose) arm, the way they looked into each other’s eyes, as loving equals. Alex Clayton amazed with this ability to jump without preparation, landing softly and with enough juice in his legs to launch into minute, delicate steps. “Funny Papers” is an example of a different but equally important strand in Taylor, his acerbic wit, grasp of caricature, and theatrical imagination. According to the program, the choreogarphy was generated by the dancers, arranged and selected by Taylor. But it is decidedly Taylor’s humor, Taylor’s worldview. The piece is set to a series of ridiculous popular songs: Popeye the Sailor, Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini, etc, to which the dancers perform a kind of satire of American cheerfulness. To Popeye, they punch the air; to the bikini song, two women feign modesty. To I Am Woman Hear Me Roar, sung out of tune, a woman kicks and flails her arms while the men behind her stand at attention and salute. (This number struck a particularly sour note after the recent election.) It seems that Taylor's dances are acquiring new layers, deepening, over time.

Jessica Ferretti in “Vive la Loïe.” Photo by Noah Aberlin.

The two middle works on the program, by Jody Sperling and Lauren Lovette, were a glimpse into the company's new path under the direction of former Taylor dancer Michael Novak. '“Vive la Loïe” is a tribute to the modern-dance pioneer Loïe Fuller, who fascinated audiences in the late nineteenth century with her manipulations of fabric and light, responding almost magically to music. It's hard to transport oneself to a time when electric, colored light was itself a kind of magic. (You can, however, see films of Fuller in action on YouTube to get an idea.) Fuller was onto something, and Sperling manages to channel some of the sensations the audience must have felt. Watching this composition of fabric, music, and light is like watching the ocean, or a fire, or wind rustling through leaves, or clouds floating in the sky. The shapes are ever-changing, full of poetic associations. That constant flow allows a kind of release, a sense of wonder, surprise, sometimes amazement. Sperling places her dancer, Jessica Ferretti, on a platofrom, where she appears to hover in the darkness. Over the course of the piece, she becomes a flame, a flower, an ocean, the Victory of Samothrace, a moth, a bird, a flag, fireworks. Yes, the sum of all this is more special effect than dance. If the piece went on for one minute longer, it would be too much. But as it is, “Vive la Loïe” is a welcome respite, like popping a pill or watching a meteor shower streak across the sky. In contrast, Lovette's “Recess,” though lovely in its designs—the translucent colored backdrops by Stadstad and silhouetted lighting by Baker are very pleasing to the eye—and imaginative in its movement vocabulary, feels frenetic and the slightest bit forced. The dancers exhibit the hyperactivity and eagerness of kids in the school yard. They race and slide and shuffle and roll, or bend and twist jerkily, with the awkardness of young animals as yet unable to fully control their bodies or channel their energies. I appreciate Lovette's impulse to embrace awkwardness and break conventional movement patterns. It feels sincere and true. But her dances tend to look like a series of explorations rather than a finished idea. The contrast with Taylor is particularly stark.

The cast of “Recess.”