The Endless Moment—A Second Viewing of Alexei Ratmansky’s “Solitude”

Adrian Danchig-Waring and Felix Valedon in Alexei Ratmansky’s “Solitude.” Behind are Andrew Veyette and Isabelle LaFreniere. Photo by Erin Baiano.

One of the most striking aspects of Alexei Ratmansky’s new ballet “Solitude,” for New York City Ballet, is the sensation it creates of disordered time. The work is based on a photograph of a father and his dead son, killed in a Russian air strike in Kharkiv. And, like the traumatic event it depicts, it seems to unfold in a kind of fissure in time, in which the real and the unreal, the internal and the external, mix and collide violently. Now that I’ve had the chance to see it multiple times, I’m even more struck by this feeling that it creates, of being untethered to a sense of past and future, or of forward motion. As the man (in the second cast, danced by Adrian Danchig-Waring) kneels next to the prone body of his son (the eleven-year-old Felix Valedon), figures move around him. But he is not connected to them. It is as if he had become dissociated from the world around him.

At first the other dancers move toward him in a line, creating jagged, staccato images, like puppets in a dance of death. Time loses its continuity and becomes a series of flashes: open chests, hands like paddles, bodies stretching away from each other or pushed together by an external force. To the sound of a vaguely martial underlying melody on the bassoon, two women are lifted up, kicking their legs beneath them. Isabella LaFreniere slices the air with her long, powerful legs, like javelins. Two dancers zig zag their knees from side to side; two others hop on one leg, holding the opposite foot. Multiple things happen at once.

All this is done coldly, without expression. The figures are like broken fragments of reality, or perhaps something more inhuman, unfeeling spirits or external forces. The father and boy remain immobile. They exist in a different reality/dimension, separated from the others by a pool of light (lighting by Mark Stanley). The women line up nearby and fall, in angular waves, to the ground as the men take aim at them with open palms, revolve their arms once, and aim again. It is like a nightmare, an infernal machine.

The music, Mahler’s “funeral march” from the first symphony, switches to a different, klezmer-like melody. The women are peeled off the ground, and LaFreniere is thrown in a dramatic arc through the air, flying for a moment, as if the rules of physics had been suspended. (Or perhaps, she is being thrown forward by the force of an explosion). Other figures are pushed from behind and slid across the floor. There is an acidic kind of playfulness to this, a cruel indifference.

The music changes again, to a misty melody for the strings and woodwinds, almost Straussian in its schmaltz. A woman (Mary Thomas MacKinnon) sits with the man, perhaps in an attempt to comfort him. He doesn’t see her. Another (Unity Phelan), an angelic figure, comes flying on, supported by a male partner (Davide Riccardo). The schmaltzy melody wilts away almost immediately, flattened by a minor key. Phelan and LaFreniere stand behind the man and his son, like guardians. Their bodies slowly curve to the side, as if time and reality, or both, were melting. And then they lead the boy away, to be tossed like a rag doll from one person to the next, until, finally on his own two feet, he walks a slow diagonal from left to right, leaving the stage—he, or his soul, has departed, leaving his father even more alone. A soldier-like figure (Devin Alberda) recedes with stiff-armed, stiff-legged steps, making his own voyage to the underworld. The man’s eyes have never left the ground.

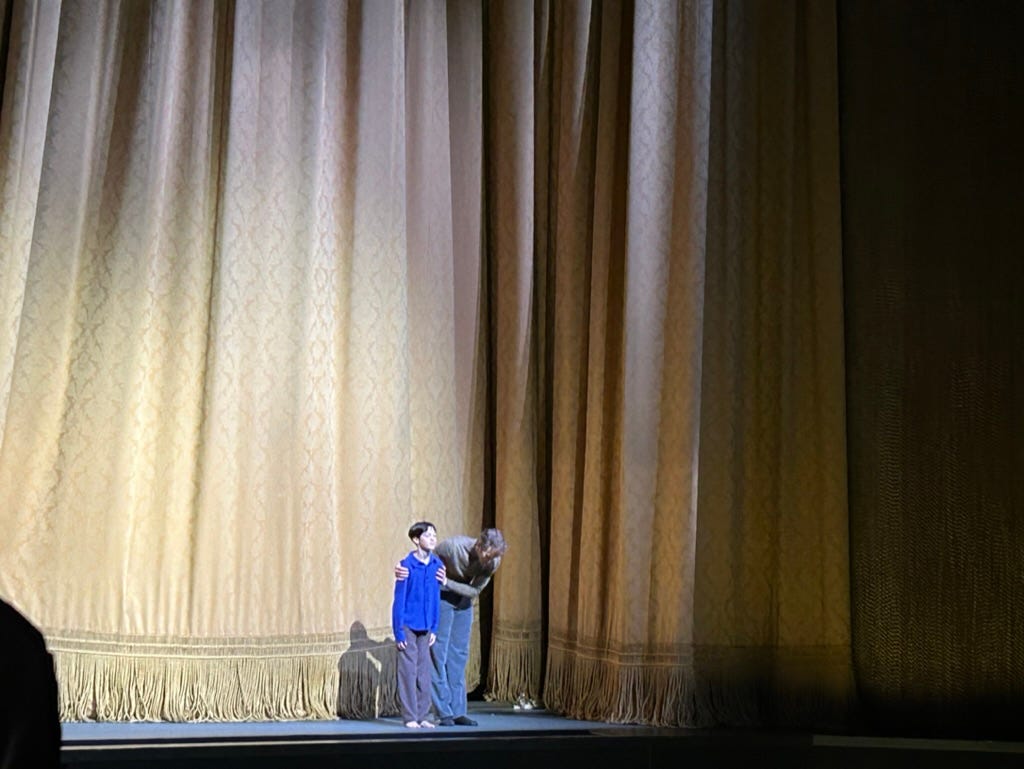

Adrian Danchig-Waring and Felix Valedon. Photo by Erin Baiano.

All this happens in part one. The audience is left unsettled, even a little horrified—the tension is almost unbearable. It’s rare to see such bleakness on a ballet stage. The fact that the action is so un-melodramatic, so cold, makes it even more difficult to take in.

During a brief pause, the black “sky” lightens a shade or two to gray, and finally, accompanied by the first notes of the “Adagietto” from Mahler’s symphony, the man rises to his feet and walks, simply, to the back of the stage. Again, the question of space and time arises. Where is he? Is this happening in his mind? Has he left his body behind? What ensues is an extraordinary solo that goes on for most of the nine minutes of the adagietto. With each slow, pulsing, extended phrase in the strings, the man seems to gather up the energy to move forward. But the forward-motion doesn’t lead anywhere; to the contrary, it seems to circle backward again and again, as if he were trapped in a place where time and movement had no meaning. He pliés deeply and rises, effortfully, into a single turning jump. He bends, falls, slides across the floor. He leaps quickly from foot to foot, but stops abruptly. He raises his arms and looks at the sky. He touches the floor. In a more frenzied passage, accompanied by a throbbing crescendo, the man waves at the sky, as if trying to call to something or someone; then he waves his arms as he lies on the ground, as if trying to bring his child back from beneath the earth. A terrible feeling of solitude descends.

When the boy finally reappears, he and Danchig-Waring execute the first steps of the man’s solo again, now together. Where are they now? Have they returned to a remembered past? Is this the moment just before the explosion that killed him? Are they in a shared place beyond death? Or is it all this at once? The tension is at its peak. The other dancers return and form a cluster, running forward, driven by a sense of panic. A light flashes and chaos ensues: bodies falling, turning, breaking. A man (Veyette) waves desperately for help in the murk. And the Danchig-Waring kneels, once again, next to the body of his dead child.

As in a nightmare, time, in “Solitude,” is both fragmented and circular. Nothing makes sense. Shards of reality and unreality come together in a strange and disquieting constellation. There is no sense of forward motion or of resolution, or even of release. The image of the dead boy and his father just hangs there, obscenely, in a kind of eternal present. “It is the saddest thing I’ve ever seen,” the person next to me said after the curtain closed. And it’s true, it is.

Felix Valedon and Adrian Danchig-Waring on Feb. 28.

Such a powerful review, thank you for sharing this, Marina. I hope I get to see it one day.

Jean: I am swept away by the painful insights in Marina Harss review of Alexi Ratmansky's new ballet for New York City Ballet titled, "Solitude.: Her insights about the ballet are pure poetry, as if on some deep level, she is the dance in words.