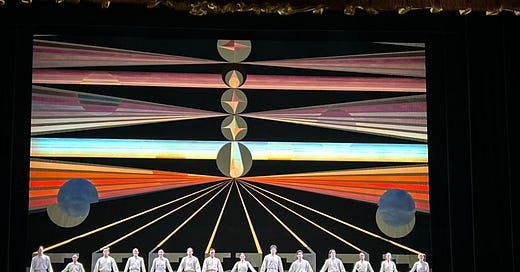

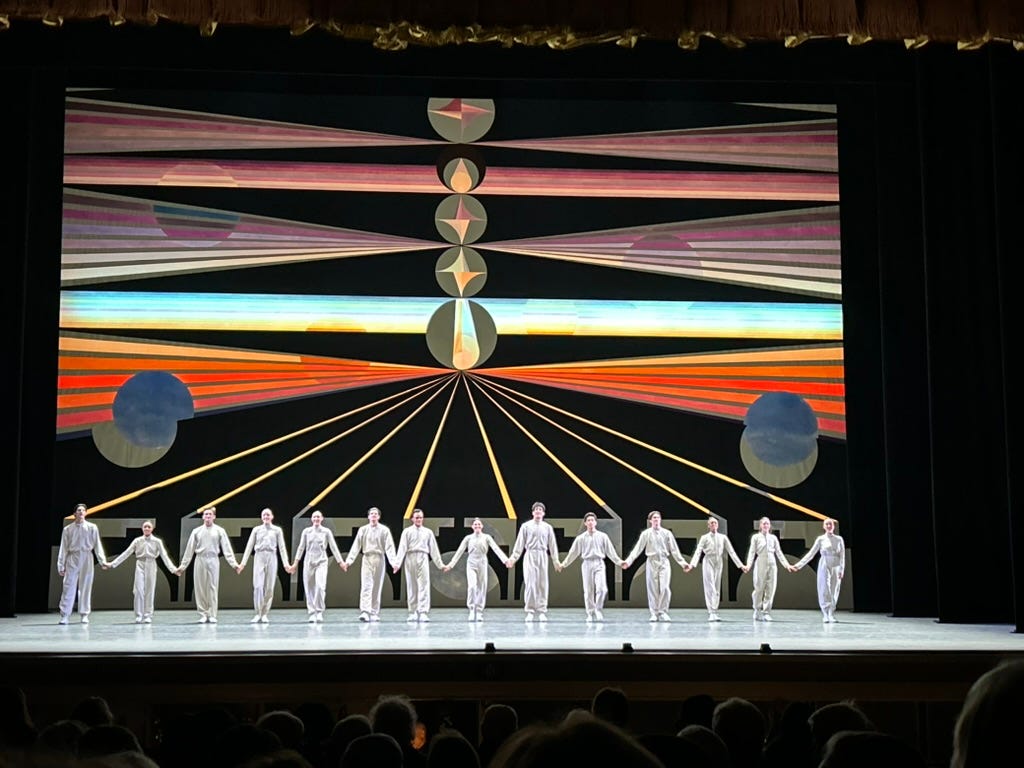

The cast of Justin Peck’s “Mystic Familiar,” with Eamon Ore-Giron’s backdrop, at New York City Ballet

The choreographer Justin Peck is on a high. He has found a style and a mode and, dare one say, a “vibe” that suits his youth-centric imagination and that also seems to tap into a hunger in the audience for works that allude to vaguely uplifting themes like hope and connection. It’s a skill, and, I’d argue, a boon for ballet, which can always use a bit of buzz. Audiences for his work are usually packed, and enthusiastic.

Peck’s most recent venture, “Mystic Familiar” is just the latest example: attractive, chic, skillfully-made, and set to contemporary-sounding, moodalicious music—this time with dreamy lyrics. The artistic elements are striking too: a semi-futuristic backdrop, by the California-based contemporary artist Eamon Ore-Giron, and cool, bright costumes by Humberto Leon, that suggest both street clothes and athletic gear. These create an appealing environment for Peck’s clean, busy, highly-patterned, geometric style.

Beneath this pleasing exterior lies the same subtext—the desire to connect to each other, nature, and the universe—that has animated previous works, from Everywhere we Go (2014) to The Times are Racing (2017) to Copland Dance Episodes (2023) and to last year’s Broadway show Illinoise. As in other Peck ballets, the dancers touch, console, and gaze at each other, or out into the audience, interacting with a slightly lost look, a mutual supportiveness that suggests anxiety but also hope. The people he depicts are young and hyper-American, sporty and nice, just kids. All this has become a kind of branding, underscored by the way this ballet is listed in the program, in capitalized letters, as “A BALLET BY JUSTIN PECK.” (Neither of the other works on the program gets this treatment. It is reminiscent of the way Spike Lee’s movies are referred to as “A Spike Lee Joint.”)

The full creative team of "Mystic Familiar.” Justin Peck is on teh right.

All in all, Mystic Familiar is a feel-good piece, athletic and bright, with wonderfully nuanced lighting by Brandon Stirling Baker. The backdrop, with its prisms of color and lines converging on a point on the horizon, suggests a utopian vision, or perhaps an imagined planetary system. The dance begins with dancers traveling from right to left in costumes with white puffy sleeves that make them look like cumulonimbus clouds traveling across the sky from East to West. This lovely image is accompanied by a wafting flute melody over strings, the first section of a five-part score by the electronic composer and singer-songwriter Dan Deacon. Later, we will hear his voice intoning lyrics like “close your eyes and become a mountain, become the skies, become the seas, open your eyes,” from the pit.

This opening is followed by the entrance, from the left, of the dancer Taylor Stanley, who performs one of the creature-like, shape-shifting solos Stanley has become known for in works like Kyle Abraham’s The Runaway. Stanley ripples, twists, turns and crouches, arms and hands cutting or tickling the air, feet barely moving from one spot. As the movements increase in size, so does the texture of the music, from solo piano to large orchestral sound. Then, as in other Peck ballets, the rest of the cast rushes on, gathering around Stanley, offering consolation and comfort. The stop-and-go transitions are reminiscent of the rhythms of musical theater: slow build to a climax, pause, new beginning, slow build, etc.

More elements follow. “Fire” is the most reminiscent of previous works, full of dancers creating intricate patterns across the stage while moving their arms busily, forming semaphoric pathways. Here, they wear sneakers and move with quick, staccato accents, as Tiler Peck and Gilbert Bolden III dance an energetic duet full of tilts and stretches. “Water” brings a meditative duet for two women, Emily Kikta and Naomi Corti, who lift and lower each other, up and down, up and down, like waves in the sea or dolphins cavorting in slow motion.

Emily Kikta (standing) and Naomi Corti (lying down) in the “Water” section of “Mystic Familiar.” Photo by Erin Baiano.

It is only the last section, “Ether,” that suggests an intriguing new direction, as the dancers enter in all-white athletic wear, like members of a sports team performing in the opening ceremonies of the Olympics. The music here becomes a repeated pattern of floating arpeggios, to which the dancers respond with minimalist, almost mathematical movements, gliding around like particles in a weightless haze. Here, the dance becomes more impersonal, almost interstellar, reminiscent of the minimalist style of Lucinda Childs in works like Dance or Einstein on the Beach.

Taylor Stanley and the rest of the cast of “Mystic Familiar.” Costumes by Humberto Leon. Photo by Erin Baiano.

Alas, just as it’s becoming interesting, Mystic Familiar abruptly ends. What might this idea have become? Could it be the beginning of a different style for Peck, more abstract, less sentimental? We’ll know soon enough. It feels like his emphasis on mutual understanding and connection may have run its course. But it’s difficult to walk away from an approach that appeals to so many.

The rest of the program was made up of Christopher Wheeldon’s From You Within Me, from 2023, and George Balanchine’s pseudo-Béjartian, absurdist Variations Pour Une Porte et Un Soupir. The latter was wittily and stylishly danced by the tall, siren-like Miriam Miller and Daniel Ulbricht, a wonderful mime. The piece, set to a score of creaks and blips by Pierre Henry, is witty and clever (though overlong). The rippling and billowing of the female protagonist’s silk cape is suggestive of Loïe Fuller’s experiments with fabric and light.

Miriam Miller and Daniel Ulbricht in “Variations Pour une Porte et un Soupir.” Photo by Erin Baiano

Like the Peck, Wheeldon’s From You Within Me boasts a gorgeous, painterly backdrop, by Kylie Manning, bathed in expressive lighting by Mary Louise Geiger. The score is Arnold Schoenberg’s rapturous Verklärte Nacht, used by Antony Tudor in Pillar of Fire and Anne Teresa de Keersmaker in her searing duet of the same name. Wheeldon’s choreography, though luscious and sculptural, fails to meet the challenge of the music. Crescendos, dark undertones, and luminous harmonic resolutions are left unplumbed. Instead, we get elegant sculptural formations in which the dancers’ bodies interlock beautifully, but that fail to communicate any significance or connection to the score. Wheeldon’s feeling for the music blossoms only in a section for male dancers that begins with a duet for Chun Wai Chan and Jovani Furlan and then expands into what might have been a very beautiful, tender, all-male ballet.

The ending, too, is lovely: As the light changes, the painting becomes a kind of landscape. Dawn arrives, and the dancers, in silhouette, gaze out over nature, full of awe. Nature has its moment.

The cast of Christopher Wheeldon’s “From You Within Me,” with its beautiful backdrop by Kylie Manning.

looove this writing… how you write the music in … also how u describe peck’s ‘vibe,’ and (gently) suggest its limitations. excellent review.

Thanks for the generous review! Yes, there were definitely a couple of strong stop-and-go Lucinda Childs/ Einstein references in Facebook & Instagram clips.