A week in New York

Glimpses of Kyle Abraham, Balanchine's Nutcracker, Caleb Teicher, and Ailey, plus a film about Loie Fuller

Like the song about the days of Christmas, this has been a week full of presents. Here are a few:

Dancing Shoes: At the Joyce, "A Very Swing Out Holiday" brings a healthy helping of joy

Samantha Siegel and Breonna Jordan in “A Very Swing Out Holiday,” by Steven Pisano.

The first thing you see in “A Very Swing Out Holiday,” now playing at the Joyce, is a slightly raised curtain, behind which a bunch of feet are happily zipping around. A jazz band wails out a series of jazzified Christmas songs. The feeling is immediately festive, inviting. This is a party you’d like to be a part of. (And you can, after the intermission.) As the curtain lifts, you see a group of 13 dancers, dancing alone or in pairs, each doing their own version of the Lindy Hop, the dance associated with swing. The show, created by a “braintrust” (as they call it) made up of Evita Arce, LaTasha Barnes, Nathan Bugh, and Caleb Teicher—all dancers—plus Eyal Vilner (bandmaster), is, on one level, just that, a dance party, backed by an exquisite band (the Eyal Vilner Big Band), arrayed in rows onstage, and featuring the glistening voice of Imani Rousselle. On this stage, music and dance have equal value. As it goes along, the show offers a sampling of all that Lindy Hop can be, in the hands of an imaginative, original group of artists. Samantha Siegel moves like a figure made out of rubber, her body curving and bending to the music. LaTasha Barnes performs an explosive duet with the drummer Evan Hyde, deconstructing the percussionists’s rhythms with her arms, shoulder, back, derriere. Two dancers, their names chosen from a hat, do a sweet, flirtatious pas de deux. A man in a Santa Claus suit offers a funny butt-dance, and Teicher or slides and skates, forward and back, legs flying (and at times, dances on pointe). The dancers pair up in different ways, indifferent to gender, and share in the partnering; in other words, everyone leads, everyone follows. These couple dances are sometimes infused with tango touches—the close embrace, the busy, intrusive footwork. For me, that works less well; tango is complicated and precise, like chess, a quality somewhat at odds with the physical freedom and expansiveness of Lindy Hop. Toward the middle of the show, the energy quiets down for a solo, both cerebral and Buster Keaton-like, by Nathan Bugh, set in silence to his humming of Auld Lang Syne. Then the temperature rises again, building toward a finale full of lifts and tosses, jumps and splits. It makes you want to stand and cheer. And that’s just part one. After intermission, the audience joins in, dancing to the big band. A joyful evening.

+++

Land o’ Sweets: On a rowdy performance of “The Nutcracker” at NYC

Curious about Taylor Stanley’s début as Drosselmeier in Balanchine’s “The Nutcracker,” I caught an 11AM matinee for New York schoolkids. Energy in the theater was off the charts. The good news is that the kids seemed delighted by what they saw. They clapped along during the formal dances in the party scene, and gave a round of applause to the young prince (Hannon Hatchett) when he magically emerged from his Nutcracker costume, wearing a dapper pink suit. They gave Hatchett another round after his mime scene, in which he recalls the perils of the battle. And how they squealed at the scurrying of the rats! (This is New York—we know rats.) I was moved, too, by the sudden hush as soon as Sugarplum (Miriam Miller) appeared, delicately gliding on her pointes. Not a peep was heard as she undertook each sequence of sideways walks on pointe, precise soutenus, half turns. The ballerina mystique is real—embedded deep in our chromosomes. True, Miller was lovely, with her soft, yielding upper body and graceful use of her shoulders and head. I just wish her dancing in the final pas de deux, with Alec Knight, had had a more oomph. (However, I appreciate her deep backbends in his arms.) India Bradley, too, had a fantastic turn as Dewdrop, light, sharp, quick, with exciting jumps and high extensions. She débuted the role last season. A little nod to Alexander Perone, a long-legged apprentice, in the tea dance, which he performed with a mix of elegance and playfulness. Balanchine’s “Nutcracker” is a perfect machine, eliciting a predictable set of responses: delight, emotion, coziness, wonder (as when the Marie and the Nutcracker boy head into the woods, to that grandiose music). Thank you Tchaikovsky, whose melodies and orchestrations feel as fresh today as they did in 1892 in St. Petersburg. Harrison Hollingsworth’s musical interpretation was a tad less accented than the norm at NYCB—interesting, since he’s also the orchestra’s principal bassoon player. And what about Taylor Stanley’s Drosselmeier? Dancey and delicate, almost sprite-like, unsurprising for anyone who knows Stanley’s dancing. I’m sure the characterization will develop greater depth over time. The kids and I will be there to see it.

+++

Subtle Currents: The Alvin Ailey company performs works by Alonzo King, Ronald K. Brown, and Amy Hall Garner

An image from "Following the Subtle Current Upstream," by Paul Kolnik.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater company has a new leader, Alicia Graf Mack, and hallelujah for that. Mack will be the fourth in an illustrious line, following Ailey, the late Judith Jamison, and Robert Battle. But she doesn’t start until next year—this season is still a product of the ancient régime. Which is just fine. I caught the Dec. 5 show, which included works by Amy Hall Garner, Alonzo King, and Ronald K. Brown. Garner’s “Century,” set to big band jazz by Basie, Ellington and others, is as frenetic and over-amplified as it was at its premiere last year. (And the un-flattering costumes!) It takes all of Alonzo King's zen atmosphere to quiet the spirit after its rather relentless deployment of steps. In contrast, King’s “Following the Subtle Current Upstream,” set to Miriam Makeba and the sound of storms and bells, creates a subtle mood. As it begins, three men slide on with linked arms. They bring to mind the three Graces. Their harmonious interlocking is broken only by the entrance of a fourth, the noble, sinuous and bounding Isaiah Day. Later, accompanied by Makeba’s stirring voice, Ashley Kaylynn Green performs a fierce solo—strong legs tracing giant circles in the air; this is followed by an extremely sexy pas de deux, all slithers and pulling and hooking of limbs. The ensembles, couched in the hyper-extended, allongé-everything vocabulary that King shares with William Forsythe, are less interesting. And what can one say about Brown’s “Grace,” created back in 1999? Every choreographer could learn from the way Brown brings dancers on and off stage, creating currents and counter-currents, patterns that appear and dissolve so organically they seem somehow preordained. The movement, mostly unisex, draws energy and impetus from the whole body, especially the back and arms—it has texture and depth and turns his dancers into beautiful beings, imbued with a combination of sincerity, cool, and serene power. At the end, the dancers form a procession. One figure, that of Hannah Alissa Richardson, is like a priestess, tending to her people. When a member of her flock, Isaiah Day, rages with his arms, legs, and shoulders, she places her hand on his back. You can feel its warming, calming effect. He knows he is good hands, as does the audience.

+++

Spirit Quests: Jamar Roberts's new "Al-Andalus Blues" and Ronald K. Brown's "Dancing Spirit" at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

The cast of Jamar Roberts’s new “Al-Andalus Blues”

I’ve been a fan of Jamar Roberts’s work since his 2017 “Members Don’t Get Weary” for Alvin Ailey. In particular, I admire his musicality—he’s partial to complex jazz—and his ability to sublimate stories and meaning through movement. And he draws exceptionally committed, un-fussy performances from his dancers. So I was looking forward to the new “Al-Andalus Blues,” his latest for the Ailey troupe. After seeing the premiere, though, I confess to finding it frustratingly opaque. The inspiration, it has been written, is the centuries-long Moorish rule of the Iberian peninsula, prior to the catholic takeover (or Reconquista), completed in 1492. It is an excitingly fertile subject. And the musical choices, a recording of Roberta Flack singing “Angelitos Negros,” based on a poem by the Venezuelan poet Andrés Eloy Blanco, and Miles Davis’s version of “Concierto de Aranjuez,” are evocative. But what to make of this dance for an ensemble of what appear to be medieval knights, dressed in what looks like armor, with crosses inscribed on their chests? Are they meant to represent the conquistadores, marching into Al-Andalus? They move like warriors, with intensity and purpose, led by the expressive Hannah Alissa Richardson. Arms slice and jab, bodies twist and curve furiously. Two men fight to the death. A platform (by Libby Stadstad) is pulled apart—does this represent the kingdom of Al Andalus being torn asunder? The stakes are high, but which side of the story is being told? While this happens, we hear Miles Davis’s endless modulations on Joaquín Rodrigo’s melodies, familiar from countless guitar concerts. But the marriage of music and dance never happens; in fact the two elements are mostly at cross purposes. One is fervent, the other exploratory; one meanders, the other drives toward something, though that goal is unclear. And so, despite the intensity of the performances, the piece drags, and we never really understand what it’s all about.

The cast of Ronald K. Brown’s “Dancing Spirit”

The same program included Roald K. Brown’s “Dancing Spirit,” his 2009 tribute to Judith Jamison. Brown borrowed the title of Jamison’s memoir, as well as an evocation of "Cry," Ailey's 1971 solo for Jamison, in which she embodied the labor and love intrinsic to the lives Black women everywhere, "especially," as Ailey put it, "our mothers." (Here this passage is danced by the lyrical Daley-Perdomo). "Dancing Spirit" is one of Brown's quietest, sparest, most inward works, set to mostly quiet music: a gentle xylophone melody, a passage for guitar, another for saxophone. (The composers include Duke Ellington, Wynton Marsalis, and Radiohead.) The dancers never look out at the audience. Instead, they dance for each other, or themselves, or the universe. The dance begins with a slow procession, led by Daley-Perdomo, in which one after another, the dancers enter, moving their arms down, up, outward, and forward. It becomes an incantation. Later, an overlapping phrase is introduced, led by Chalvar Monteiro, in which he slaps the air with his arm, sharply, creating a new layer of rhythm. (The layering of rhythms is one of Brown's special talents.) Monteiro and Daley-Perdomo, lead spirits, share a gorgeous duet of slow turns and arabesques. Gradually the stage fills with dancers, each engrossed in his or her own world, alone or joined by a few companions. They are like planets, each on its own orbit. As often happens in Brown's work, the dancers look like gods. Monteiro, Daley-Perdomo, and the explosive Ashley Kaylynn Green in particular. You are never sorry to have seen a piece by Ronald K. Brown.

+++

The Ages of Man: On Kyle Abraham's new work, "Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful," at the Armory

After “Dear Lord, Make me Beautiful,” at the Park Avenue Armory

The Park Avenue Armory is a special place. The final Merce Cunningham performances were held there, an epic event that filled several platforms laid out across the gargantuan drill hall, which fills an entire city block. As was De Keersmaeker’s thrilling exploration of the Brandenburg Concertos, and Bausch’s Rite of Spring performed by dancers from the École des Sables. Compared to these, Kyle Abraham’s Dear Lord, Make Me Beautiful is a calm, intimate affair; intimate, despite the enormous size of his canvas. A dappled projection, by Cao Yuxi fills the back wall and floor of the space, like a waterfall pouring down from the ceiling and toward the audience, who sit on risers. To the side, atop a platform, are the musicians of yMusic, a combination of strings, woodwinds, percussion, and at least one saxophone. The dancers emerge from wings that have been built along both sides. Abraham doesn’t feel the need to overpopulate the space. If I had to pick a single word to describe “Dear Lord” it would be spacious. The dancers move in a way that suggests looseness and air within their joints that allows them to expand into the world around them. They lope, they glide, with silken ease. With the help of Cao Yuxi’s visual design, Karen Young’s flowing costumes, and the lighting of Dan Scully, they appear to merge into the dappled landscape, through which they swim like schools of fish or soar like birds flitting across the sky. Impossible not to think of Cunningham’s Summerspace, with its dappled Rauschenberg design, except that here the colors are in constant movement, like light shining through leaves or water. Like the shifting musical landscape in which the dancers move, the work suggests the changing seasons. Abraham, who dances throughout, alone and as part of the group, appears to be reflecting on the different phases of life: the eagerness of youth, the knowledge of adulthood, and the moments of isolation, doubt, and vulnerability that come with age. As well as everything in between: relationships, beauty, the accumulation of knowledge, nature. At the start, he traces circles around the space, gleefully at first, then with confidence and abandon, and finally with a kind of laboriousness. He is young, he is old. (Without meaning offense, I was reminded of an old Marcel Marceau classic, “Youth, Maturity, Old Age, and Death,” that I once saw live and left me in a puddle of tears.) Here, life comes and goes in a constant flow, like the tides. “Dear Lord” is the dance of a man looking back on a life, like Taylor’s “Beloved Renegade” or "Robbins’s “Watermill,” except that Abraham is more honest about the anxiety that comes with such reflections. He often looks glassy-eyed, even lost. What is missing in his depiction, perhaps, is the uglier side of life—here, all is beauty, intimacy, tenderness. Perhaps what Abraham wants to render beautiful is not so much himself as the entire world.

+++

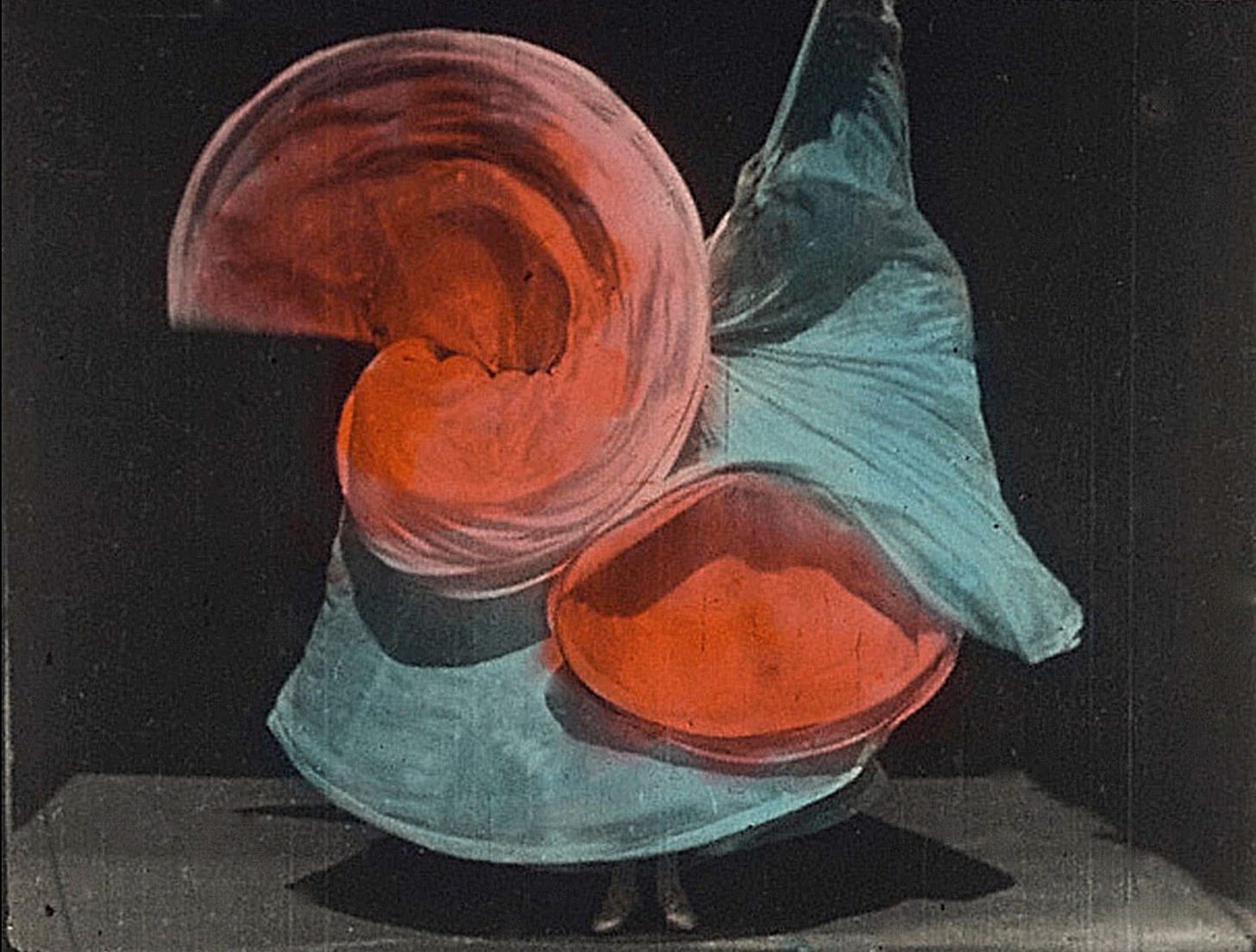

Incandescent: "Obsessed with Light" is a new film about the wizard of movement and light Loie Fuller

Film still of Loie Fuller’s “Serpentine Dancer”

Loie Fuller—dancer, choreographer, innovator in theatrical lighting, entertainer, illusionist—is having a moment. I’ve recently seen not one but two dance pieces inspired by her experiments in fabric, movement, and light. In these works the body becomes an ever-changing landscape, bathed in color, somehow, magically, expressing the currents in music. It’s not hard to imagine the effect these billowing waves, set in motion by the dancer, had on Fuller’s first viewers, in late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century Paris and Berlin and New York. The trick behind the magic is simple and quickly understood, but the effect is nevertheless fascinating, like watching flames or wind blowing over a field of grass. The transformation happens in our imagination. Electric light, then new, was made even more exciting by the use of surrealistic combinations of color. Now there is a documentary, “Obsessed with Light,” directed by Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum, that gives Fuller her due, as an innovator, not only in dance, but in the technologies of the stage. Fuller’s influence, it turns out, is everywhere. In the puppetry of Basil Twist (creator of an abstract Symphonie Fantastique); the stage illuminations of Jennifer Tipton; the fashion of Iris van Herpern; the pop spectacles of Taylor Swift and Shakira; the choreography of Moses Pendleton and Ruth St. Denis. Most obviously in the work of Jody Sperling, whose Loie-inspired choreography is seen throughout the film Not many artists, even far greater ones, can claim such influence. The film is both informative and a beautiful watch, mainly for its period footage: semi-nude Duncan dancers, acrobats, vaudeville performers, and Fuller in her various guises. “Obsessed with Light” is at the Quad Cinema.