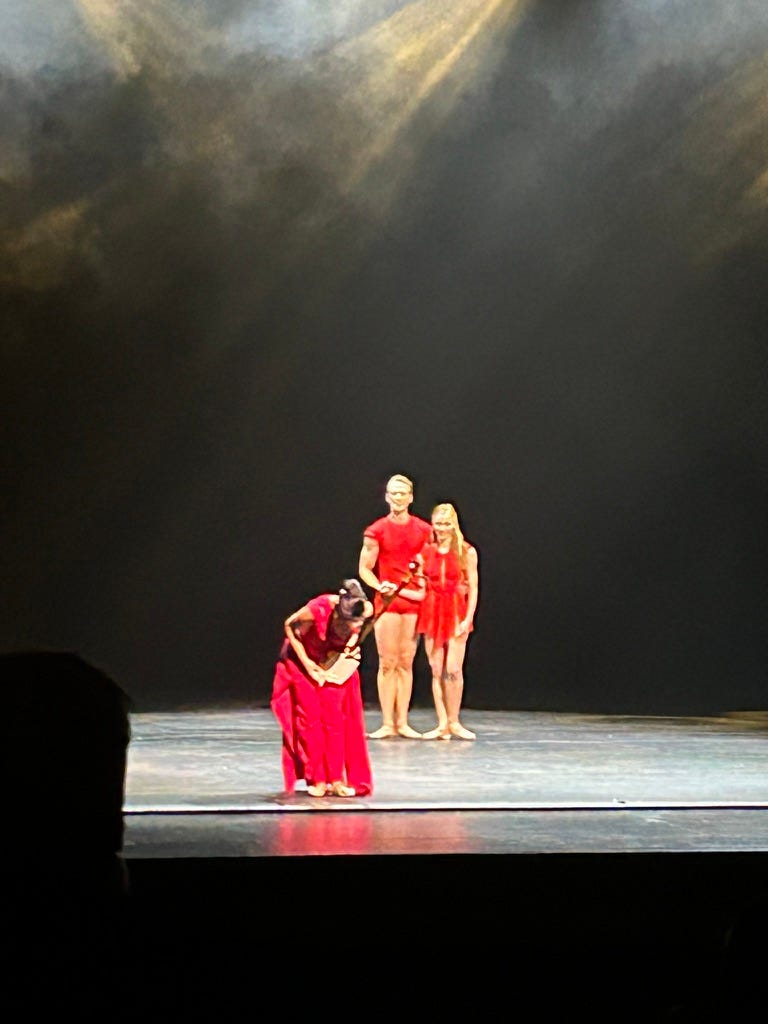

Raskolnikov’s Dream

A Balletic Treatment of Dostoevky at American Ballet Theatre (and more on the fall season)

Cassandra Trenary in Crime and Punishment. Photo by Quinn Wharton

One of the questions a new ballet based on a work of literature inevitably faces is: Does it make a case for itself? Why do it? Novels are particularly difficult to illustrate through dance: They deal in complex ideas, expressed through words, with plots that acquire many layers and introduce new characters, new situations, new meanings.

It is a perennial problem and the main one that confounds the ballet that premiered this fall as part of American Ballet Theatre’s season, Crime and Punishment. As the title indicates, it is based on Dostoevsky’s convoluted, psychologically extreme portrait of the student Raskolnikov—a consciousness in distress—who breaks the rules of society by committing an act of atrocious violence while at the same time seeking moral and spiritual transcendence through self-sacrifice. Dostoevsky’s novel is a challenge. Its main character spends most of its pages in state of near delirium. And it is even more difficult, today, to find one’s way into Raskolnikov’s melodramatic cast of mind, the whys that push him to his inexplicable actions.

Not to mention the novel’s rambling structure, full of colorful characters and over-the-top episodes that seem to tumble out in indiscriminate order. “I do not object to soul-searching and self-revelation,” Vladimir Nabokov, a Dostevsky skeptic, once wrote of Crime and Punishment, but “the soul, and the sins, and the sentimentality, and the journalese, hardly warrant the tedious and muddled search.” One thing is sure: It does not cry out for balletic treatment.

The choreographer Helen Pickett and her collaborators (especially her partner in direction and story treatment James Bonas) have bravely taken it on, but as the curtain comes down at the end of the evening, the question remains. Why do it? Does it bring us closer to the novel? No. Does it interestingly delve into Dostoevsky’s themes of moral degradation, alienation, social inequality, and redemption, or help us understand them? No. Does it create compelling characters? No. Does it at least engage the viewer’s imagination? Not really.

The result is a meandering ballet that feels longer than its two hours, in which scene follows scene follows scene, creating a never-ending series of events: Raskolnikov squirms in his bed as he thinks back to his crime; he seeks solace from a friend; a man dies a protracted death; Raskolnikov confronts his sister’s suitor, an arrogant burgher who dances with big lumbering steps; crowds mill around a city office; a detective snoops; a slithering ne’er-do-well eavesdrops, insistently proposes marriage, and eventually shoots himself in the head.

There is an awful lot of stage action, aided somewhat by supertitles that help explain is going on, but fail to give a sense of how these events are connected. “Family in desperation clings to hope.” “A funeral and a death.” Who are these people? The death of a secondary character, Marmeladov, requires two scenes to complete, and is the occasion for two dances of desperation by his wife (one accompanied by coughing, the other by gasping), before she too expires. There are no less than 16 soloist characters, each of whom has at least one soliloquy.

Those soliloquies emerge through movement that is a kind of pantomime-dance-acting, executed through mostly unspecific gestures meant to convey a state of mind. Say, Raskonikov’s confused, violent delirium: sharp, flailing movements for the arms, curved torso, falling, collapsing, twisting. The dancer in this role (Cassandra Trenary on opening night, alternating with Herman Cornejo and Breanne Granlund) is trapped in a kind of everlasting semi-feral episode, like a wild-haired tumbleweed that rolls from scene to scene. Sonya (a beautiful and touching Sunmi Park), a destitute young woman forced into prostitution, executes aching enveloppés to express her despair. Claire Davison (Sonya’s mother), kicks and falls and reaches out with splayed fingers. The detective Porfiry (Thomas Forster), slinks and dives, when he’s not flying in great jetés across the stage. The jeté gets a lot of action, standing in for longing, fear, desperation, force of will.

The never-ending action is kept moving along through the use of mobile partitions and a few simple elements like tables and chairs, repeatedly pushed around by the dancers (designs by Soutra Gilmour). A door sometimes appears upstage, at the summit of a large staircase. Projections (by Tal Yarden) bring us back to the crime. We see the faces of the two old women, Raskolnikov’s victims, and the silhouette of the axe with which they are killed. Blood streams down one woman’s face. A ticking clock marks the passage of time. An eye—the eye of the state no doubt—watches closely. It’s sort of Buñuel-meets-Pyscho-meets-Ingmar Bergman.

The music, by Isobel Waller-Bridge—sister of the creator of Fleabag–sets the scene, as in a movie or a tv series. Rhythms, bells, the growling of an electric guitar; a little jazz syncopation for the tavern scene; in the more tender moments, passages for cello and viola. What the music does not do, because it has not been asked to, is create space or motivation for dancing. With the exception of a few pas de deux and a couple of ensembles numbers, the production leaves very little space for dancing. It’s more of a pantomime than a ballet.

The palette is gray and beige, suggesting a kind of bleak, timeless, proletarian netherworld, shot through with a few elements of color: Sonya’s yellow skirt, the damning bright red blood stains on Raskolnikov’s rags.

Somewhere in the middle of the first act, I found myself thinking back to the Soviet dramatic ballets, like Spartacus, in which, as here, the characters express themselves through a simplified vocabulary meant to express extreme states of mind. Yes, the sets here are less kitsch, but the manner of storytelling, and the proportion of dance to exposition, is not so different. Nor is the way that the corps is used, as a form of stage furniture, filling the space with mostly unison movements: revelry at the pub, frustration at the government office, the ambling of the faceless crowd in the street.

Here, as in those Soviet ballets, the pas de deux becomes a space for the exposition of conventional emotion through partnering. One sees promenades and arabesques, and lifts in which the woman’s body arches beautifully in the air. In the end, the women here are given as little room for variety of expression as they are in any number of other, earlier ballets: They are beautiful, and vulnerable, and victimized, and true. In the end, Raskolnikov (Trenary) is saved by Sonya’s sacrificial love and by her faith in god. As the curtain falls, we see them kneeling together, accompanied by sentimental music, holding onto each other for dear life.

Just before, as Raskolnikov had emerged from the cage in which he had been held for his crimes, I had a thought. Is this really the moment to make a ballet based on Crime and Punishment? I cannot have been the only person in the theater to think of Alexei Navalny, a real person left to die in a prison camp in Northern Russia, this very year, not for a crime imagined by a novelist, but for standing up to the State, in the real world of contemporary Russia. Or of the way Russia aggressively asserts its cultural importance in the world and imposes it upon its neighbor. Is this the time to create a new ballet based on one of the Russian classics, without finding some deeper meaning in its story, the story of an individual coming to pieces in a cruel, oppressive world?

+++

More on American Ballet Theatre’s fall season at Lincoln Center:

On Balanchine’s Sylvia Pas de Deux…

Chloe Misseldine and Aran Bell in Sylvia Pas de Deux. Photo by Emma Zordan.

George Balanchine created his Sylvia Pas de Deux for Maria Tallchief, then his wife and leading ballerina, in 1950. It’s seldom seen (the last time it was performed at NYCB was in 1994), but suddenly it is being performed both at American Ballet Theatre, and, soon, at New York City Ballet as part of a tribute to Tallchief during the company’s winter season. It feels like a bit of an oddity, and in fact, seeing it performed at ABT these past two days it has hardly felt like Balanchine at all. The affect of both of the casts I saw was almost exaggeratedly ingratiating, full of charm. The dancing felt soft-focus. Gillian Murphy’s rendition, with its flutters and softness, was almost Ashtonian. Chloe Misseldine was all loveliness and delicacy, everything just so. Her dancing produces a sense of wonder: such beautiful turns in arabesque or attitude; such soaring grand rond de jambe, held for an extra moment before coming down; such effortless balances. Her working leg went through three distinct positions when passing from front to back. Not to mention the striking beauty of her face. Aran Bell, Misseldine’s partner, soared through the virtuoso male variation: cabrioles, turning cabrioles, double tours to second position. But I loved the delicacy with which Camargo had imbued his steps the night before, his legs touching softly in the air with each cabriole, giving him an extra puff of lightness. (His landings from the tours were less perfect.) I’m not sure I know what to make of the ballet itself. It seems to lack a point of view—the thing I most associate wtih Balanchine. I wonder what it will look like at NYCB, where I imagine Megan Fairchild and Tiler Peck will be among the dancers who will perform it.

On Twyla Tharp’s Sinatra Suite…

Daniel Camargo and Sunmi Park in Twyla Tharp’s “Sinatra Suite.” Photo by Emma Zordan.

What a surprise to be so moved by this performance of Twyla's Sinatra Suite by Daniel Camargo and Sunmi Park at American Ballet Theatre. As he did in Of Love and Rage, Camargo strikes me as an extraordinary actor-dancer, a performer who relays the quality of thought and inner life and complex, shifting emotion with amazing clarity and simplicity, both through his face and through his dancing. Each movement means something, and takes just the right amount of time to express that meaning. Added to that, he is such an able, engaged partner; with him, partnering becomes an expressive art. In this performance of "Sinatra Suite" I felt I could see his every passing thought: a sense of rapture in "Strangers in the Night," a powerful romanticism in "All the Way," disenchantment and roughness in "That's Life," loss in "My Way," and an almost unbearable hurt in "One for my Baby." He played that final solo with the looseness and swaying imbalance of someone who has had too much to drink, but within that tipsiness there was also reflection—we could almost hear him thinking. The pauses between movements suggested conflicting currents. He stopped, he started, he fell, then rose up and opened his hands, as if thinking, “what’s left of all of that?” A swooning lift in "All the Way," held for an extra moment on the word "aaaaaallll," made me hold my breath. SunMi Park was a perfect partner: fresh, game, confident, even a bit teasing at times. The two of them flowed together. She seemed happy to go along for the ride.

On Alexei Ratmansky’s Neo…

Sumie Kaneko (shamisen), Catherine Hurlin, and Jarrod Curley after a performance of Neo.

Half the fun of Neo, Alexei Ratmansky's chic new pas de deux for American Ballet Theatre, is the score: a solo for shamisen (a kind of Japanese banjo) by the Japanese composer Dai Fujikura. Its insistent patterns are both suggestive of step patterns and also full of a kind of solemn wit, like the sound of Gertrude Stein’s voice reciting absurdist poetry. At ABT this season the shamisen is being played onstage by Sumie Kaneko. Throughout, its twanging sound is the third character in the dance, originally created for Isabella Boylston and James Whiteside during the pandemic as a video short produced by The Joyce in 2021. Seeing it live now, the dance's witticisms stand out all the more: flat-footed stomps and pawing and shuffling for the feet, wave-like movements of the arms. The two dancers, Catherine Hurlin and Jarod Curley here, engage in a funny repartee that is at times competitive, at times friendly, at times completely silly. At one point, Curley "plays" Hurlin's leg like the string of an instrument, plucking it as if to produce a sound. Or they swing their legs like metronomes, illustrating the loops in the score. She droops in his arms like a noodle, then re-constitutes herself and pushes him down to the ground. The technique is often extreme—in many ways, with its giant battements and leg circles and stretches, “Neo” is like a Forsythe pas de deux, though more playful and less mannered in affect. In fact, it's a sort of companion piece to Ratmansky's 1998 "Middle Duet," which derived its inspiration from Forsythe while softening the Forsythian edges. But where "Middle Duet" was sly and sleek, "Neo" is cheeky and light, full of quick, skittering steps and careening combinations that fly across space. The swish of Hurlin's long pony-tail, knotted high on her head, is part of the game. The Japanese music and flexings of the wrists and feet are also reminiscent of another early Ratmansky ballet, Dreams About Japan, an abstraction of a series of Kabuki plays that Ratmansky made for Nina Ananiashvili’s touring ensemble. It’s clear that this music frees his imagination and releases some of his zanier tendencies, which is all to the good.

Thanks, Marina, as always for your review. I saw Cornejo as Raskolnikov, and felt that his powerful performance lifted the choreography, giving it a fierceness it didn't have on its own. Actually, I was shocked when I learned that Trenary had danced the premiere and basically received all the reviews, as did Park and Shevchenko as members of the opening -night cast....My bete noire were the "contemporary" arms and the fact that nobody was ever still. Does anyone remember how Fonteyn and Ulanova would just stand still in R&J as they realized the seriousness of the events they had set in motion while the music swelled bigger and bigger around them? So simple, so theatrical, and so full of emotion.

As always, thank you for putting into ballet words what I often fail to vocalize. What an ‘interesting’ fall season indeed!